No other river best captures the diverse nature of Missouri than the St. Francis River. The river begins its 426-mile course in the St. Francis Mountains, flows rapidly in its rugged upper part, before taking the appearance of a typical Ozark river, then ends in the flat swampy country of southeastern Missouri and northeastern Arkansas. It marks the boundary between Missouri and Arkansas along the west side of Dunklin County, then eventually reaches the Mississippi north of Helena-West Helena, Arkansas.

The St. Francis was known to indigenous peoples by its Choctaw name—Chobohollay, or Chollohollay, meaning smoky water. The French name was St. Francois, which likely came from the time of the explorations of Father Marquette and Louis Joliet. It is uncertain whether the name commemorates St. Francis of Assisi or St. Francis Xavier. Marquette was a Jesuit, so it is more likely the latter.

Indigenous people settled in the river valley by 12,000 years ago. However, the first historical reference is the mention of a mound encountered by the de Soto expedition in 1541—now preserved as Parkin Historic Site in Cross County, Arkansas. The presence of vast areas of giant cane along the river in times of early European settlement indicated widespread prehistoric agriculture, abandoned when indigenous people perished from European-introduced diseases beginning in the 1500s. French explorers found lead along the upper St. Francis in the 1710s, promoting French settlement.

“Old Settlers” Cherokee moved into the area in the 1780s and settled in the region. The earliest group of Chickamauga Cherokee led by The Bowl came in 1794. A second group of nearly 1200 followed in about 1810. Shawnee, Delaware, Quapaw, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and other tribal groups settled the area by 1810. The productive and game-rich lower St. Francis became one of the focal points for an economy based on hunting, fishing, and trade. Besides natives, Creole French, those who escaped enslavement, and American traders and hunters occupied this region at the time.

The St. Francis was originally a route for moving furs and minerals out and other goods into the interior of what became Missouri. In the words of one French official, “…since St. Francis was navigable during the rainy seasons, by placing … lead on pirogues near the mines, it would reach the Mississippi River in eight days.”

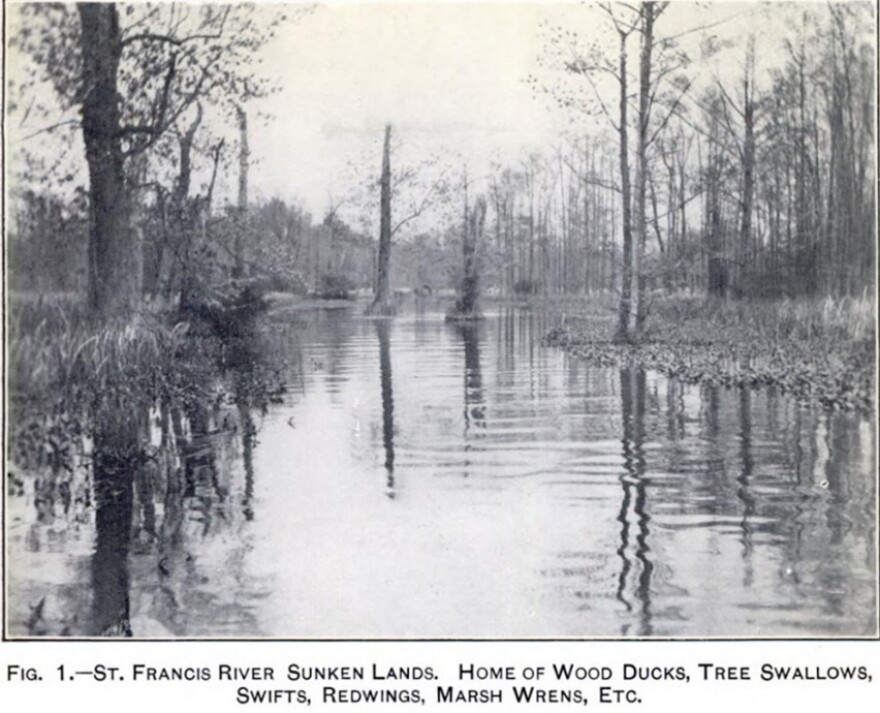

However, the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811-1813 greatly altered the river. What had been a seasonally flooded swamp forest along the river became the St. Francis sunklands. Trees toppled, and blocked the original channel, impeding flow and navigability. According to Arthur H. Howell, “large forests were prostrated, immense fissures were formed, and profound changes took place…”

The results included the destruction of the Cherokee settlement on St. Francis River and disruption of their main travel route. These people moved into northwestern Arkansas as a result. Sinking, fissures, sand blows, and downed timber restricted easy access to the entire middle St. Francis for the remainder of the 1800s.

Missouri Congressmen repeatedly tried to obtain federal assistance for clearing the channel to allow navigability of the St. Francis, without success. While small steamboats were able to ascend other Ozark rivers into southern Missouri, this never happened on the St. Francis.

Seasonal flooding and the slow, meandering flow of the middle St. Francis prevented settlement and agriculture along the St. Francis in Missouri. The river has now largely been controlled by a combination of drainage, ditching, and the construction of Lake Wappapello in 1941.